When my oldest son, Eric, was born on the last day of the year in 1970, there were over a dozen people present. Three women, Joan, Irene and my sister Vickie, were my support team. They were great: rubbing my legs, holding my hands, reminding me to breathe with the contractions, feeding me ice chips and most importantly, insisting that the midwife follow the instructions I'd given about how this birth was to be conducted. The rest of the people were friends and acquaintances there for the show, since if they really cared about me they would have realized the inappropriateness of such a public moment.

Birth and death are the most obvious of sacramental moments. I find it ludicrous that the hippie movement, which avowed love to all, has been instrumental in degrading the celebration of these rites of passage into a frivolous affair. The other contributing factor is medical technology, which makes laboratory procedures of these mysterious doorways into and out of the life we know. For this reason, many churches and other social organizations are urging the writing of living wills, which describe in detail the acceptable behaviors leading up to and following the time of one's death. I didn't feel the need for such a document until the death of my son in November of this year.

Eric had been fighting colon cancer for 3 years and was gradually losing the battle. This last year, our family just naturally came together more often, as we sensed that we didn't have long to do so. I'd finally made plans to make extended visits to Tennessee where he lived to be able to be with him. There wasn't a lot we could do, maybe a few chores to ease the strain on his girlfriend, who was continuing to work at his insistence. Mostly I just wanted to spend as much time with him as I could. I often felt the old mama bear rise up in me, looking for new treatments or alternative cures, but Eric felt he was getting the best available. My sisters suggested we look into hospice for help and counseling, but that didn't seem appropriate. Eric chose the manner in which he wanted to live his days and the rest of us followed suit. He rarely spoke of his disease or its course, but was open and humorous about the various indignities of his condition (like wearing diapers.) When his stepdad tried to talk to him about death he responded with, "Those are your issues, Dad." In my desire to love him, I allowed Eric to guide me.

We all, including Eric I believe, were hoping and expecting another month or two. When I visited in early November I was shocked by the difficulty he had breathing. Yet when he fell asleep his breathing eased and he said his oxygen level was still so high they wouldn't give him a tank. Whenever he did anything, even going to the bathroom or making some oatmeal in the microwave, he ran short of breath. I guess my attitude was one of denial, as I didn't believe he was so close to his last. After a visit of 10 days, I flew home to Denver on November 14th.

Four days later, on Saturday I called Eric and got his partner, Bill, on his cell phone. Eric was on his way to the hospital. He'd been coughing uncontrollably. Many phone calls later the family in Tennessee was alerted and on the scene at the hospital in Nashville. That evening we got the news from the doctor that the obstruction was the tumors and there was little to be done. I flew out at midnight.

Arriving at the hospital, I went to see Eric in the Intensive Care Unit. He was awake and humorous as usual, breathing with the help of an oxygen mask. Much ado was being made over his care: intravenous drugs and fluid, constant checking of vital signs and anything else he might request. The crew that was assembling in the waiting room consisted of his immediate family (dad, mom, two brothers, sister, sister-in-law), Carrie's mother and aunt as backup for her, and Bill and his crew, which consisted of his girlfriend Samantha and gofer, Cruz. Later Eric's close friend Jer arrived with his girlfriend, Sadie, and their baby. We worked it out with the nurses over how many people could be in his room. A couple of times the nurses appropriately kicked everyone out to let him rest. Gradually his oxygen level worsened.

At first the nurses were going on the theory and practice that Eric's condition could be stabilized. Their actions, like limiting visitors, were with that in mind, and seemed to help. But eventually, with only Carrie present, it became obvious that he was not going to come out of this. We got to the point when the hospital would have put him on a respirator, which would essentially render him unconscious and unable to make decisions. The staff warned us that they might not be able to get him off it. Finally late Sunday night, a doctor heard Eric's statement that he declined the respirator and wanted no resuscitation. The doctor then took me aside to verify that this was in accord with my wishes. I agreed. The doctor, a kindly older man, said he believed this to be the best decision and that he suggested we fight for this. His words surprised me, indicating there might be some resistance. Fortunately, there was none.

Since we had turned down the next steps to be done in heroic life support, Eric was moved to the oncology unit. During this move, he was using a small oxygen tank, which couldn't put out the amount of oxygen he'd been using in the ICU. With all hands alerted to make the move as quick and uneventful as possible, he was raced down halls and up 3 floors to his new room. The nurses there were very kind and helpful. They set our crew up in a "family room" a few doors down from Eric's room and let us do as we pleased, always ready to answer questions and fetch supplies or assist us in Eric's care.

Carrie was at Eric's side almost constantly from the time he arrived at the hospital. She tried to get a bit of sleep, even crawled up onto the hospital bed with him Sunday night at his insistence; she shared with him completely his last days. The selfless love she exhibited was inspirational. When I commented how much of a heroine she appeared to others for having stayed with Eric through his operations and illness, she answered that she didn't know how anyone could do otherwise. At the funeral she said she received her strength from Eric himself.

The second person by Eric's side at first was Bill. He was having a hard time cutting loose of his good friend and partner. He liked being in charge and taking care of things, though, so his grief seemed to be lightened by the services he provided for Eric's family and friends. Bill had become very hostile with one of Eric's brothers and myself earlier in the year, after his girlfriend, who was the daughter of our friend and teacher, had left him, so we hadn't spoken for awhile. For the purposes of this meeting, we put the past aside as we attempted to make Eric's way through this passage as smooth as possible. As more family members and Jer arrived, we took turns as the second person by his bed. After we'd moved to the oncology unit, as many people as wanted were allowed in the room.

Eric had told Bill the only people he wanted there besides his family were Carrie, Bill and Jer. Cruz and Samantha were very sensitive to this and only went in to see him once briefly. Carrie's mom and aunt stayed in the room with her, but as her backup, rubbing her shoulders and bringing her food as she sat by Eric's right side, holding him and talking to him.

After moving to oncology, Eric became still quieter, concentrating on breathing and integrating the sensations he was experiencing. Shortly after the move he became very agitated, said he had to throw up and tried to sit up. He took off his mask and was giving us requests we didn't fully understand. He also said he was afraid. A nurse came in and told us to back off and not crowd around him as much. She said since he isn't getting enough oxygen the presence of so many people up close is suffocating. After this I tried to give him more space and only sat by him if there weren't already 3 or 4 people there.

I felt I could be with him even in the waiting room, meditating on his presence, slowly attending to my breathing. This emphasis on breath was very strong sitting with him as well. Though conversations would sometimes go on around him, the powerful focus of his breath filled the room.

On Monday when Eric was being moved, his brother Si and Mary, Si's wife, were out of the hospital getting some sleep. When Si walked into the room in the Oncology unit, Bill said to Eric, "Here's Si." Eric said, "Hi." It was the last he spoke. Silas took up his position of the previous day at the head of the bed, rubbing Eric's neck and shoulders. Even as Eric became less able to communicate, his desire for Silas to hold this position was evident, and he stayed there until the end.

At one point Sunday afternoon, he said, "I want to go back to 1970." I thought, of course, that's when he was born. Carrie misunderstood him, and thinking he was delirious, because he was fiddling with the mask, thought he was requesting a change in the settings for the oxygen. She fiddled with the outlet valves in the mask and told him he was going back to 19 or 17. A bit later he said he wanted to go back to 1980, not 1970 whatever. That year, when he was 10 years old, was probably a happy time for him. We'll never know exactly what he was thinking then. My belief is that he was seeing things from a different perspective than we, and in trying to communicate them, was being frustrated. Late Monday afternoon, he said, "You should try this sometime," and then took off his mask and told Carrie to put it on. My inclination at this time would have been to let him do whatever he wanted, but she fought with him to put the mask back on.

I believe both Carrie and Bill were even more attached to Eric than the rest of us and had a harder time letting him go. He hadn't wanted to go to the hospital, but Bill and Carrie had insisted. It would have been hard to watch him go through the dying stages without feeling he had as much life support as possible. The hospital seemed to get out of our way after we';d moved from ICU, but I'm not sure he wanted the amount of drugs he had at the time of death.

Sometime Monday afternoon, in response to Eric's agitation, the nurse had given him dilaudid for pain relief and atavan for the anxiety. His ability or inclination to speak and interact with us decreased until he lay still with his eyes half open, breathing steadily but with great effort. At first this was a little freaky, as it seemed he wasn't as present as he had been. I asked a nurse if it was due to the drugs. She said she thought it was part of the dying process. She said she believed he could hear us and it would be a good time to speak to him. Her brother had been in a coma for awhile once and afterwards he told her he'd heard everything that was said around him. He hadn't felt that he'd left his body but heard everything with a sense that it was about a third person. I told everyone about this; at first they all got very quiet as they realized Eric could hear them, then resumed their conversation as they realized it was okay.

I felt I had an unseen guide throughout that day. If I felt the need to be near Eric or see him I would go into his room. If I the room felt too crowded, I'd leave and go to the family room. I'd look to see what needed to be done, both for my own needs and anyone else. I suspect I was fleeing the discomfort I felt in the group by finding other things to do.

Around 8:30 I was talking to someone in the family room when Bill and Abner came running in. "Come!" they urged and ran back. We all followed, also at a run. "It's time," someone said. I ran up to Eric, laid my hand on his and kissed his cheek. "I love you honey, I always will. We'll always be with you. Go to the light." Then I backed away and let someone else say goodbye. We stood around him and watched him not breathe, yet seemingly present. Soon there were several sharp intakes of breath, almost mechanical, arching his neck. Then stillness. A nurse had arrived, perhaps when she saw us all running in? She checked his pulse after each intake. Finally, I saw/felt a release, a glow move upward from his head, then a great calmness. I knew my son had died. The nurse checked again, then whispered in Si's ear, "He's gone."

We all sat there for a minute in awe. Then I felt a restlessness, we didn't know what to do next. I suggested Martin do the reading from the American Book of the Dead. I explained a bit about it and he began. I realized the nurse had said she was going for the medical examiner, so I went out to make sure the reading wasn't interrupted. At the nurse's station I answered some questions for her and asked that we have an hour. She agreed to wait until I returned to page the official.

When I arrived outside the door to Eric's room, I found Carrie with her mom and aunt and Bill. They were discussing the reading, as Carrie was afraid she wouldn't be able to have a few minutes alone with Eric. I assured her we had all the time we needed, explained why I'd left during the reading and apologized for not asking her about the reading or what she wanted to do. Basically I hadn't want to drag her away, but had asked Bill who thought it would be okay. I wanted to give Eric any help we could in the bardos and thought the readings were a good way to do it. Martin was prepared to do them, would stick with it all the way through and had even introduced Eric to the sound of a gong. (Eric had given him the gong for Christmas.)

After Martin finished the reading, we went in and cleared everyone out to give Carrie some space. When she left, different people spent short periods of time there, but much of the time no one wanted to be there. As Carrie had said, "He's not there anymore." I felt uncomfortable with having no one there, so sat there alone for awhile. I talked to Eric and sang lullabies.

This part is hard for me to write because I don't feel good about it. Late in the afternoon, or early evening, a friend of Martin's had arrived, ostensibly to bring some food. He went down to meet her in the garage, then brought her upstairs and into Eric's room! Cindy was her name and she is a 'certified heart rebirther.' She'd done some 'work' on or with Eric and she and Marty were convinced that her work should be continued at Eric's deathbed.

Cindy walked in as if she owned the place, set up a tape player and started playing a tape of gongs, very loudly. Several people asked her to turn it down which she did. We were all in shock. I assumed it was okay for her to be there, as I suspect others did too. Only later did we discover that no one except Martin wanted her there. She had given Eric some massage, which he liked, but since he never mentioned it to anyone else, we doubt he really wanted her there. I left after she set up the music so I missed some of her method, and when I returned, she was standing on his left side, waving her hands over him. She said, "Right now he's very expanded, and I'm just clearing him out," as she moved her hands in a sweeping motion. I walked out again.

After Eric was gone, people milled about in the family room and the hall, gradually gathering belongings and leaving. Several conversations concerned people's reaction to Cindy, all which were similarly negative. Eric's brothers were quite upset with Martin for not bringing her into the family room to meet everyone and clearing her presence with Carrie before taking her to see Eric. Bill went kind of nuts and ran around telling everyone what belongings or money of Eric's they were getting. Our family discussed what and how we were going to proceed. Martin had already made connections regarding retrieving his body from the hospital and the burial on the Farm. I insisted we rent a van rather than use Martin's old van. I wanted Eric to ride in style. We decided to meet the next morning at the hospital.

When I was about ready to leave, I went into the room where Eric was, to shoo Cindy out. She'd brought the food and her paraphernalia there and left it there the whole time. I felt she'd invaded. Trying to be nice, I ended up listening to her tell me about her heart rebirthing experience and how she came to this line of 'work.' At first I thought she did this regularly and exclaimed how good a thing it is to help people die. Then I discovered she'd never attended a death before and felt severely had. I wish I'd been more discriminating and outspoken earlier. Perhaps I could have helped smooth Eric's passage. Martin holds that he died shortly after Cindy had done her 'work' with him, to which I contend that perhaps she chased him away. Actually, I believe it was his time.

So you can see how deluded humans respond to this sacrament. I cannot claim innocence myself.

The next morning I wrote in my journal: "The unthinkable, undeniable, unbearable, unfathomable has happened. Eric left us around 8:45 last night. In peace. A disparate group of people he loved and who loved him gathered to help his passing, cling to him and grieve....

"Go in peace, Eric, Peacemaker, beloved son and friend. May your passage be calm, may you connect with your former good karma and incarnate for the benefit of beings. May you cultivate your connection with the Dharma and incorporate the compassion and wisdom of the Buddha's teachings into your next life and all that follow it. May all who know you benefit from your love and truth and your droll humor. May we all bring these qualities into our lives so we can be better people."

Over the next couple of weeks I often pictured Eric walking in the bardo. I spoke to him, offered him food and visualized him in the company of two dakini guides. I found this activity very helpful, as it's hard to accept the fact that someone you love is gone, just gone, period. I couldn't get into the idea of heaven and angels (or of hell and demons.) I'd heard the teaching in the Book of the Dead that the crying of loved ones tears at the being of the dead person. I noticed that grief at times took the form of a release of energy and at others of clinging. Tears were shed either way. When I felt the clinging, when I missed him the most, the idea of reincarnation and the bardo was comforting.

After a few weeks, I no longer seemed to need that support. I even find it difficult, almost spooky, to imagine my son continuing in any cohesive way. I don't know what happens after death. If the bardos exist as the teachings say, and they are taught by people I respect very much, the being in the bardo isn't Eric. I say the prayers and offer him food not because he's my son, but because I can help in this way. All beings become our children.

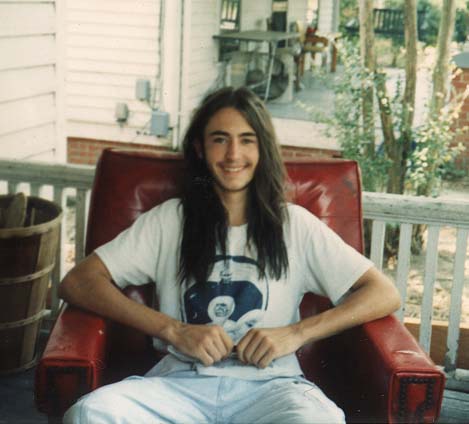

Now I'm gathering a review of his life. I've placed photos of Eric everywhere I frequent. I look at them often and I marvel at his life. It does something to your mind to see a life from conception and birth, through such growth and change, decay and death. Through so much passage of time comes a timeless perspective. A month after he died, I wrote:

May I be all things

May I be all things